This past week we taught Freedom’s Feast MLK Day materials at the Kipp Ujima Academy and the Reginald F Lewis Museum in Baltimore. The idea was the same even though the learners and teaching partners were different in each place. We’ve worked hard to gather interesting resources to help Americans celebrate six national holidays and there are many ways to use them. We don’t create lesson plans because we believe that fixed lesson plans lead to dull learning. A lesson plan reflects the person who writes it, not the person who receives it. Instead, we encourage “feasters” to adapt our resources to fit their needs. Every classroom, home, teacher, family, student, and learning environment is different. How could one lesson plan possibly fit all situations?

What we wanted to do was to celebrate Dr. King, the movement he played such an instrumental role in leading and the possibility of children and adults discovering what these achievements might mean for them today. At Kipp Ujima Academy, we used “The Children March” ceremony. Several children served as the readers and leader for their classmates which gave a few students in each of four classes the chance to read out loud in front of their peers and try on their performance chops. Discipline is a big Kipp value as is earning a privilege like this. Some were comfortable, others struggled but all were proud to be chosen. This important skill--public performance--could be practiced with a friendly group of peers but still carried the freight of a formal role.

|

| Mr Reese and students read "The Children March" ceremony |

At key moments, Alex Reese, their talented "Teach for America" teacher, and I stopped and used selected illustrations from one of our book list recommendations to support an open discussion about a core concept, event or historical figure. The range of media from watercolor representations to historical photos stimulated lively discussions around “segregation,” “Ruby Bridges,” “prejudice,” to name a few. A student asked whether any percentage of color in your skin made you “colored.” I wanted to tell him he should ask his Mom but told him instead that the custom in our country is that if you have some African American blood in your inheritance you are generally considered to be African American. He didn’t think that was “fair.” A longer session would have allowed us to follow that detour. One girl was filled with outrageous indignation when we discussed sit-ins. “Who were they to tell us where we could sit to eat our meals at a public restaurant? Or anywhere? That’s just plain wrong!” I complimented her on her passion and conviction. The subsequent back and forth banter soliciting definitions led to the volunteer who said that a “conviction” is “when you get sent to jail” which provided the opening to talk about multiple definitions and context. These discussions don’t come ready made in a lesson plan. They happen because you are willing to dance a little with your students. You get on the floor together and you move to the music. You may not cover the whole floor but everyone might remember the exhilaration of the dance because you are all involved and responding to the same music.

We also used a basic internet connection and projected Alex’s laptop image to use ceremony hyperlinks to view video of “The Children’s Crusade” in Birmingham. Student reactions launched discussions about injustice, the role of television and most importantly the role of children in the movement. The fixed ceremony gave us the structure for a conversation with a beginning and end. Gifted children’s book authors and illustrators provided a range of artwork that helped us to discover the depth of knowledge and insights our groups possessed. And students were excited to share the civil rights experiences grandparents and elders had told them about when they went home with Table Talk questions earlier in the week. Those shared memories gave them a meaningful personal context to bring to the historical discussion. When we connected service to the legacy of Dr. King it wasn’t a stretch. Asking them to do homework overnight by thinking about the different ways in which they might focus on and express their service commitments made sense. It was an extension of their month of work on service at the school. Our service medallion project that brought all 120 students together in the cafeteria the next morning was a good deal more chaotic than any of us would have preferred. But in the end, students made duck tape bracelets or medallions they were excited about.

|

| Our two student helpers |

|

| I(heart)tutoring |

|

| "Help Out" heart medallion (shy artist) |

|

| Scavenger hunters share their museum observations |

At the Museum, we had a different opportunity and challenge. We had the wonderful resource of the permanent exhibit but couldn’t be sure who would participate even with advance registration. Our final group of children ranged in age from 5 to 13 with young parents and grandparents. A ceremony with a diverse group of strangers can be alienating so we opted for an open ended discussion about Dr. King with prompts using illustrations from our book list books to highlight concepts we wanted our guests to search for in the permanent exhibit:” segregation,” “prejudice,” “non-violent protest,” “civil disobedience.” Then we sent our visitors out with clipboards and staff prepared questionnaires to find examples of these concepts in the exhibit. Aided by enthusiastic young docents, the exhibit came alive in new ways. Participants connected it through the lens of the movement and our discussion. They were finding evidence through pictures and artifacts that these things happened in our own community. We put tools in their hands to make deductive leaps, to connect all the dots.We weren’t telling. They were discovering.

|

| Excited artists wait for shrinky dinks medallions to finish baking |

They asked questions we hadn’t anticipated and answered many of the ones we had. We ended with making shrink dinks service medallions , an arts exercise so inviting and well set up by the museum professionals that even the adults couldn’t resist. One little boy asked, “How do WE shrink?” That one stumped me for a second. I smiled at him, grinned at the elders in the audience and responded, “Get old.”

|

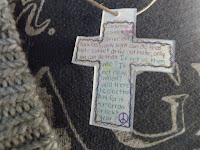

| medallion with quotes from ceremony |

We still emphasized the special role of children in the movement. This theme captures children's attention and imagination. It lets them build a bridge from a distant historical moment to the present in their quest for meaning and purpose. The world that Dr. King fought to change is so substantively different from the perspective of most youngsters today that they often don’t understand what the struggle was about.

And yet, if children half a century ago could move the needle on history then perhaps they can too! The belief that our convictions can lead to actions that make a lasting difference is such a crucial and exciting lesson for young citizens in our democracy. That Dr. King could inspire other children to march across time to bring our children this message is the finest thing I can think of on this holiday to celebrate.

No comments:

Post a Comment